To promote a peaceful transition to a Cuba that respects human rights

and political and economic freedoms

Appeasing Cuba’s Regime Didn’t Work over 42 years and the dangers of underestimating the Castro regime

Despite the claims made by some, U.S. - Cuba relations have not been static over the past 62 years, and Congressmen Michael McCaul and Mario Diaz-Balart authored an important OpEd in The Wall Street Journal that is a must read on April 2, 2021 titled "Appeasing Cuba’s Regime Didn’t Work: The Biden administration should learn from the failures of the Obama administration". However the history of failure did not begin with Obama, but stretches back several decades that offer important lessons for policy makers. It also necessitates dispelling some myths.

Batista in the 1950s was not a U.S. backed dictator, but was pressured out by Washington in favor of what they believed would be a return to democracy

In a previous CubaBrief explored the negative reaction of the Truman Administration to Fulgencio Batista's March 10, 1952 coup against the democratically elected government of Carlos Prio, and in another the Eisenhower Administration's engagement with Havana during the Batista regime, from January 20, 1953 through December 31, 1958. Batista, during this period was not "backed" by the United States, but decreasingly tolerated, with an arms embargo placed on the Batista government by the Eisenhower Administration in March 1958, and the US Ambassador pressuring the Cuban strongman to leave office in December 1958.

Richard Nixon met with Fidel Castro in April 1959 and sought a detente with Havana in 1974

Through the first two years of the Castro regime the Eisenhower Administration's approach to Cuba changed dramatically from quickly recognizing the revolutionary government on January 7, 1959, Vice President Richard Nixon meeting with Fidel Castro for three hours on April 19, 1959 at theVice President’s formal office in the U.S. Capitol. Nixon, following the meeting summarized the conversation and reached the following conclusion:

“My own appraisal of him as a man is somewhat mixed. The one fact we can be sure of is that he has those indefinable qualities which make him a leader of men. Whatever we may think of him he is going to be a great factor in the development of Cuba and very possibly in Latin American affairs generally. He seems to be sincere. He is either incredibly naive about Communism or under Communist discipline—my guess is the former, and as I have already implied his ideas as to how to run a government or an economy are less developed than those of almost any world figure I have met in fifty countries.

Following a series of hostile actions by the Castro regime over two years the Eisenhower Administration severed diplomatic relations on January 3, 1961.

Relations between Cuba and the United States would reach historic lows, never reached again, during the Kennedy Administration with the Bay of Pigs invasion in April of 1961 and the Cuban Missile Crisis in October of 1962 when the world came the closest it has come to a nuclear holocaust.

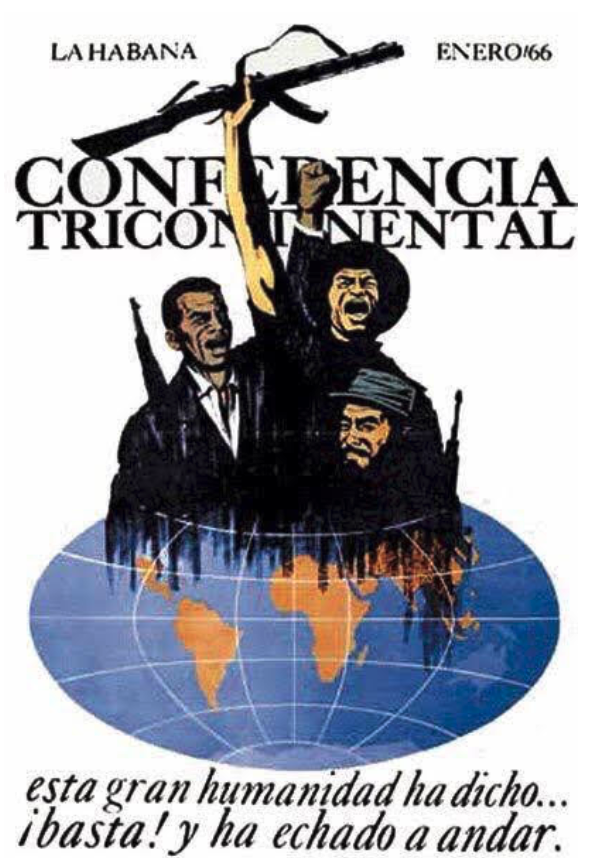

Poster for the 1966 Tricontinental meeting in Havana, Cuba

The Castro regime organized the first Tricontinental Meeting in Havana in January 1966, gathering guerrillas and terrorists from Africa, Asia, and the Americas to organize a worldwide movement against bourgeois democracies and to advance international communism by whatever means necessary, including international terrorism. Relations between Cuba and the United States remained cool and hostile throughout the rest of the 1960s.

Warming of relations between Washington and Havana did not begin until the tail end of the Nixon Administration, following the start of detente with China and the Soviet Union. Nixon traveled to China in February 1972 and met with Mao Zedong dropping opposition to Beijing's entry to the United Nations, and in May 1972 Nixon traveled to the Soviet Union and met with Leonid Breshnev and supported a nuclear arms agreement. National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger had laid the groundwork for both meetings, and the overall detente.

In 1973 Henry Kissinger assumed the position of Secretary of State while also retaining his position as National Security Advisor in the Nixon Administration, and began to explore the possibility of a detente with Fidel Castro. Nestor T. Carbonell, in his important 2020 book Why Cuba Matters: New Threats in America’s Backyard, describes what happened next.

“Cuba remained a controversial political issue in the United States, so Kissinger guardedly looked for an intermediary to make initial contacts with the Castro regime (as President Kennedy had done with journalist Lisa Howard following the Missile Crisis). The choice this time was Frank Mankiewicz, a freelance journalist and former spokesman for Robert Kennedy who had recently shot a documentary on Cuba for CBS and was returning to Havana to interview Castro…” According to Kissinger, Nixon was not enthusiastic about the emissary, but he went along with a message to Castro along these lines: “America in principle was prepared to improve relations [with Cuba] on the basis of reciprocal measures agreed in confidential discussions … and was willing to show our goodwill by making symbolic first moves.”

Fidel Castro responded to the outreach with Mankiewicz with a box of Cuban cigars for Kissinger and a message expressing interest in “relaxing tensions” – the definition of détente. In the meantime, Watergate led to the early departure of Nixon from the White House on August 9, 1974 and Gerald Ford, his vice president, replacing him. [However, Nixon continued with both positions through November 3, 1975, and as Secretary of State until the end of the Ford Administration on January 20, 1977.]

“A preliminary meeting was held on January 11, 1975, at a cafeteria in New York, by Deputy Undersecretary of State Lawrence Eagleburger with two Castro representatives: Ramón Sánchez Parodi, a senior official of the Cuban Communist Party, and Néstor García, first secretary of Cuba’s UN mission. This was followed by a substantive discussion on July 9 at the Pierre Hotel in Manhattan, led by Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs William Rogers, who covered some of the steps approved by Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to relax tensions, phase out the embargo, and normalize relations. […]

“Eager to clinch a deal with Castro, the Ford administration offered several inducements to the Cuban ruler without any quid pro quo. First, the United States voted in favor of the July 29, 1975, OAS resolution, effectively ending the multilateral diplomatic and economic sanctions against the Castro regime. Then on August 19, President Ford eased the US embargo, allowing foreign subsidiaries of US companies to trade with Cuba, dropping foreign aid penalties on countries trading with the island, and permitting ships en route to Cuba to refuel in the United States.”

The hoped for "easing of tensions" did not occur, but instead the Ford Administration ended up with egg on its face.

Castro’s response was to send thousands of Cuban troops to Africa, first to Angola. According to the [Department of State Bulletin Volume 89 - February 1989] On September 23, 1975 “Secretary of State Henry Kissinger declared that events in Angola had taken a ‘distressing turn’ and that the United States was ‘most alarmed at the interference of extracontinental powers,’ i.e., the Soviet Union and Cuba.” [ Cubans had been there since at least March 1975]

All pretense that Cuba only had an advisory role was dropped on November 5, 1975, [Department of State Bulletin Volume 89 - February 1989] when thousands of Cuban troops were fighting in Angola; by February 1976, the number had increased to an estimated 14,000.” Cuban involvement in Angola would continue until 1991.

Kissinger was so angered by the Cuban intervention in Angola, and the failure of detente that he entertained the idea of air strikes on Cuba.

Pattern of failure with Havana has been one of providing unilateral concessions to the Castro regime in the hope of normalized relations in return.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario